Here I sit, seven weeks after the close of my residency, and not one word has escaped me to land on the blog about it. This is frustrating, as has also been the transition back to “real life.”

“Don’t incinerate on re-entry!” one of my new friends said, as we dispersed our separate ways at the end of August. But I don’t come equipped with a fire extinguisher: in many respects, I am nothing but cinders…

But even ash can be used for other purposes. What it needs, and what I need, is the proper structure—an intervention, if you will. Before the building goes up (or is renovated), the scaffold does.

Scaffold, a definition:

1a : a temporary or movable platform for workers (as bricklayers, painters, or miners) to stand or sit on when working at a height above the floor or ground

2 : a supporting framework

A schedule that wasn’t

The Vermont Studio Center, where I did my residency, doesn’t create a program or participation requirements for its residents. They provide readings: both resident and visiting artist; and slide nights: for residents and visual artists. You can take it or leave it; the selection is a la carte and completely up to you. If you like, you can sign up to spend time talking craft with one of the visiting artists or writers, but you don’t have to do that, either.

In fact, the closest VSC comes to creating a schedule are the daily meals: breakfast, lunch, and dinner happen at the same (limited) time of day, Monday through Saturday (Sunday gets messy due to brunch). You can choose to skip these too; hunger is your own business. While I was there, people skipped breakfast all the time. Personally, I am highly motivated by food. I am also motivated by my slender wallet. The residency fee included all meals, and I didn’t want to pay for food twice.

Little though this was in terms of structure, the meal schedule put an anchor to my days. I knew I could bank on food being available at a certain time every day. I could set my watch by it. My only contribution to my schedule was to slot my creative time into the spaces around meals.

It might not sound like much, but in effect, this was a big deal.

Observation

Because I had no work to do at my residency other than my creative work, I could try out different habits and techniques, and observe what worked. That was the gift of the scaffold.

I found myself doing the same types of work at the same times of day. My night owl-ish nature also became obvious. We had a number of early birds in the writing crew while I was at VSC: people who showed up at their studio before breakfast, sometimes. I was not one of them.

Sure, I can be awake during the morning, but I never got long-form prose writing done during this time. I love the mornings for organization: making notes, analysis, research… editing. The morning is the best time for me to edit. Anything brainless — laundry, cleaning, sweeping, returning library books, photocopying — is great as well.

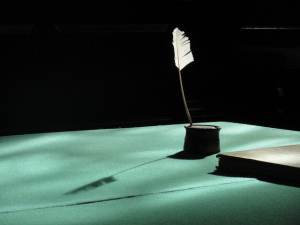

Since editing requires material to edit, I sometimes had to go to my backup plan. I’d research—preferably not online. I’d browse encyclopedias and dictionaries (dictionaries of biographical information, encyclopedias of proverbs, to name only two). If I wanted the sensation of pen in hand, I could sit by the river with my notebook and collect lyric fragments for use or expansion later: a thought here, a metaphor there, a brief description, a melody, a quirky bit of humor.

In the afternoon, the writing began. In truth, the dinner schedule proved to be an obstacle for me, because I usually got going in a flow in the hour before the meal was served. I would have loved to keep going with the writing, but I knew I’d pay for skipping the meal later with frustration and ill humor. Not to mention hunger pangs.

And the evening, following dinner, was my creative sweet spot.

Loss and rediscovery

Since I’ve come back to my regular life, I’ve lost that scaffold. I’ve learned I’m good at letting creativity slide. After all, there are bills to pay…

Unfortunately I’ve realized I pay in other ways, too. When I let the creativity go, frustration and resentment build up and fester. These nasties eventually manifest themselves in my professional, as well as persona life (I am, ironically, a much better business person when I’m being creative).

The better news is that, if I make up my mind to, I can create a new scaffold. I can set up a structure that allows me to honor both my work, and my work. This is perhaps the biggest gift of my residency.

What steps do you take to scaffold your creativity?

Like this:

Like Loading...