Honestly, there’s not much “new” news to add about preparing for my writer’s residency, other than, to quote Dory from Finding Nemo, “Just keep swimming, just keep swimming…” At least, on the writing front. However, there is another side to writing, and that is reading.

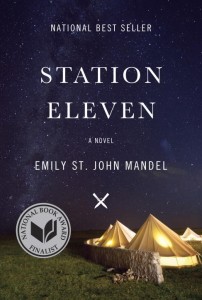

While toiling away on what passes for my current manuscript, I’ve thundered through an increasing number of books. Recently, I completed Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel.

Station Eleven was a book I added to my “to-read” list near the end of last year, when everyone and their grandmother was coming out with end-of-the-year best-of lists. I’m not sure what list I found Station Eleven on. It was an early list, that much I know, because after a while List Exhaustion set in and I couldn’t care less who ranked what where.

I realized, after I received my copy (the wait list at the library was over 200 people when I added my name) that I’d previously read one of Mandel’s other books, and I didn’t like it. The characters annoyed me. Fortunately, Station Eleven was different.

Station Eleven displays a gift for the revealing detail. The story is also good at answering only those questions that require an answer. I liked this book a lot, and my inner Nerd Writer was pleased, also. My inner Nerd Writer is on high alert ever since the residency news came in, and I’m happy to appease her whenever possible.

Choosing what questions to answer

In Station Eleven, Mandel created a “post-apocalyptic” setting. This is a novel about a not-too-distant future in which society has collapsed after a global pandemic. Making assumptions about a theoretical future can be either inspired or a disaster. Fantasy and scifi books by definition permanently must run this gauntlet. Mandel keeps the premise probable by doing the opposite of what most writers want to do: she refrains from going into (too many) details (too early).

Because of her setting, she has a large territory to explore: what aspects of the collapse of civilization will we learn about? One of the failings of writers in this position is often the summary statement (“and then, Russia fell, and when the satellites stopped working there was a long period of confusion…”). Instead, Mandel avoids giving a third person omniscient perspective — what I think of as the “newscaster view,” in which you can imagine a network talking head getting us up to speed. Instead, we learn about aspects of the collapse and the aftermath while we are meeting the characters. Mandel answers only the questions directly relevant to these people, and this saves us from falling into an encyclopedia.

The relevant detail

I’ve thought a lot lately about what goes into a vivid, submersive description. How can we show what our written world looks like, and the people in it? How much is enough, and how much is too much information? We’ve all seen those books where character descriptions run like a police profile: height, weight, eye and hair color. Mandel almost falls into the opposite trap: we get few physical character details, and by the end of the book, I confess I still wasn’t sure what some of the main characters looked like.

Oddly, that was mostly not a problem. Information about characters, their flaws, their preferences, are sprinkled throughout Station Eleven. The effect is cumulative: as we move forward through the story, we get to know more about the characters, just as we do when we meet another person repeatedly in real life. By the end of the novel, we know a lot about who these characters are (which I think is more important), and the contours of the world they live in.

Mandel does this by choosing precise details, and leaving out the rest. The trick is, I think, to be specific. Instead of saying “flowers,” say “tulips.” Instead of writing about every aspect of scene composition, pick out a handful of details that can stand in for the rest, the way a stage set can be minimal and suggestive at the same time. Station Eleven is full of selective detail. True, Mandel doesn’t veer into botany, but she does use specific nouns for her scenes and constructs a suggestive, rather than exhaustive, set.

Know your story

In the end, I think these two strengths come back to the basic premise, “Know your story.” Mandel can do more with less because she knows what her story is about. Station Eleven is a quiet book. The action and confrontation that drive the plot are conspicuous by their absence from the page — characters are witnesses, but the reader is not. This is both good and less so. On the one hand, Mandel runs the risk of losing the reader. On the other hand, explosive action is not what the book is about. Station Eleven is about what happens to the human heart and the human condition in unusual circumstances. I think Mandel stays true to that bedrock foundation. A worthwhile read.

== ==

What do you nerd out about in the books you read?